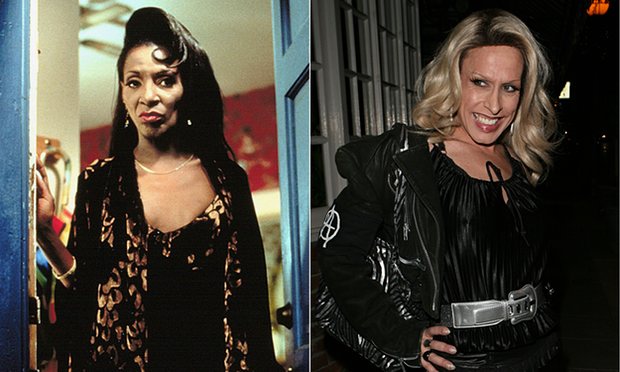

In the last week, America lost two pioneering transgender women entertainers: Alexis Arquette and The Lady Chablis... Both women had nuanced, complicated and shifting understandings of their own genders. Perhaps reflecting the time in which they grew up, over the course of their lives both used (or had applied to them) a wide variety of labels, from “drag queen” and “female impersonator”, to “transgendered” and “gender suspicious”. Yet no matter what words they used, both were always vocal advocates for trans people, rights and representation.

Read MoreAnyone in any loving relationship should get the legal benefits of marriage

Formal inequality – the kind that’s written explicitly into law – must obviously be undone. Yet I can’t help but feel that we’ve gotten the right answer to the wrong question. I have no problem with marriage as a religious tradition, or as a non-religious communal expression of love and commitment. Give me a fancy dress, lots of flowers and an excuse to day drink anytime. But it’s poorly designed to be a modern civil institution. Allowing gay people access to it makes it a little more fair, but it doesn’t make it any more just.

Read MoreHow Auntie Mame changed my life

My grandma loved me as much as anyone ever has or will, but she was raised in rural, religious Ireland, a country so theocratic that she had no birth certificate, just baptismal records. I was her kin, but when I caught her worried glances in the mirror, I knew she was trying to understand the thing that neither of us could say.

Read MoreTo end violence against trans people, the police must stop perpetuating it

Like the ticking hand on a clock, violence against trans women (especially women of color) is so routine we barely hear it.

Read MoreSettling down is the scariest part about growing up.

I am a master at leaving.

The first time I left home, I was four years old. Without telling anyone or asking permission, I carted all my toys up the stairs to where my grandmother lived – on the second floor of our house in the suburbs of New York City – and declared that I lived with her. Over the following decade, I did – and that was 10 times longer than I would stay in any one place for the next 20 years.

Read MoreWho gets to write gay rights into the history books?

But teaching queer history – developing a canon of thought about ourselves, for presentation to the world at large – presents some conundrums: Which stories will we teach? Who will choose them? And how will they be told?

Read MoreMy oasis is a garden in which nothing survives but the flowers I always hated

First published in The Guardian, August 3, 2014. Read the original here.

We grew common begonias when I was little: in terra cotta pots tucked on occasional tables, as borders around the “real” plants (irises, lilies, pansies, impatiens and endless roses), and in the shady areas in the lee of the porch where little else would flower. Growing up, begonias - waxy of leaf and spindly of stem, whose washed-out flowers seem to retain only the memory of color – were everywhere.

And how can anyone love a common begonia?

I hated the vulgar fleshiness of their red stems, how meat-like they looked; I despised the ones with leaves the color of brackish water, a muddy indeterminacy at the intersection of red, brown, and green. Begonias seemed to revel in those cast-off colors that you only find in bargain basement clothing, never anything pure or bright.

Every summer my brother and I were conscripted to work under the careful tutelage of my mother, father, and grandmother (who’d been raised on a subsistence farm in Ireland). We were the only house in our small suburban town to tear up our lawn and replace it with a food garden in which we grew tomatoes, peas, squash, and strawberries, corn, watermelon and even gooseberries over the years. It was a comfort to my grandmother, a revelation to my city-raised parents and a character building experience for my brother and I – about which we loved to complain. Aside from the year that we tried to dig a hole to China, my brother and I mostly spent the summer weeding, watering, and harvesting crops growing in between the ever-present begonias. I learned to love sun-warmed strawberries and peas straight from the pod – and to loathe begonias, which seemed neither pretty nor functional enough to be worth the space we gave them.

A few years ago, I received a genuine Manhattan miracle: an affordable ground-floor apartment with a private backyard. But miracles can be messy: my tiny slice of the great outdoors was little more than a trash heap when I moved in. Its hard-packed dirt was covered by a glittery lawn of broken glass, dotted with a few scraggly trees whose branches held more plastic bags then leaves. To this day I can’t plant so much as a marigold without digging up a broken bottle, a bent syringe, or the twisted plastic packaging of some bygone snacky-treat. The soil is bad, the direct sunlight is nearly nonexistent, and, six inches down, there is a mysterious and haphazard layer of concrete that bedevils my every effort at landscaping.

It is my perfect piece of paradise.

In my first year there, pretty much everything that I planted died: raccoons (yes, raccoons) dug up the bulbs, the seeds never sprouted, and a thriving ivy shrivelled to nothing a month after being potted. Local cats used my mulch as kitty litter, and workmen from next door accidentally poured lead paint dust on my lavender. The holly got a fungus, and the strawberries were besieged by spit bugs. The only thing that did well was a poison ivy vine – thick around as my wrist – which slowly tried to pull down the fence that separated my yard from the construction site next door.

But then there were the begonias, which my mother had recommended and my boyfriend had purchased. I’d given them a gimlet eye but dotted them dutifully around the yard, figuring I was writing their death sentence in potting soil. But in shade or partial sun, in the ground or in a pot, the begonias persisted.

Begonias, I discovered, were dependable. No, not just dependable – indefatigable. In the hot heart of summer, when the pansies fainted like fops in a Victorian novel, the begonias sat squatly undisturbed. They flowered before the lilies burst into showy banana-yellow blossoms, and were still flowering when those yellow petals showered to the ground … six days later. They adapted to being overwatered, but, like a middle child, were also fine if forgotten for a week.

And there were weeks when I forgot to tend my private paradise. I never realized how much time it takes to keep up a garden (even a tiny Manhattan-sized one). As a child, gardening seemed like a fun summer pursuit, at least for my parents; as an adult, I couldn’t figure out how they worked full-time, raised three boys, ran what sometimes felt like a halfway home for our enormous extended family, and maintained a beautiful garden.

The answer, it turned out was begonias (and impatiens and geraniums) – common flowers that we could afford and that were easy to maintain. While my parents carefully tended their roses and the crops that we ate, almost everything else we planted (I have since learned) were the super troopers of the botanical world – flowering cockroaches that can survive anything.

And who doesn’t love a survivor? Let the horticulturalists raise fickle exotics, high-maintenance orchids, and all the other divas of the dirt. I want a peaceful refuge, not one more stressful thing that demands my constant, unwavering attention. Perhaps a fancier garden would be easier in a perfect, south-facing plot, with soil that hadn’t spent 100 years accumulating city toxins and trash. I suspect I’ll never be able to afford to find out – but the begonias and I are content.

Each year I still try a few new plants: some make it and most don’t. Every time some fancy new flower wilts and dies while I watch helplessly, I’m simply left with a better view of the begonias. The more I look, the more I see that maybe their colors aren’t washed out, just subtle. It takes time to appreciate a begonia – time that I have because they are there, in full flower, from March to October, a constant flower for an inconstant gardener.

This wonder of the world has turned off. Are you worried about the climate yet?

First published in The Guardian, July 17, 2014. Read the original here.

Even before I was a travel writer, I approached sights described as "magical" with a good deal of skepticism. Too often, I have been promised miracles and delivered slights-of-hand – the usual bravura and bluff of tourism. The bioluminescent bay in Vieques, Puerto Rico was one of the few places that made good on its promises. Maybe the only one. By day, the warm shallow bay looked unremarkable, even somewhat dingy compared to the crystalline waters of nearby Caribbean beaches. But at night, the flash and spark of the tiny phytoplankton in this Mangrove lagoon filled me with literal awe. It was like living lightning.

Since January, however, the bay has gone dark – and no one knows why.

Theories abound, as a number of articles have explored in the last few months: too much human usage, or strong winds that have disturbed the bay's infinitesimal inhabitants. Like many rare ecosystems, bioluminescent bays are fragile, and the shifting patterns of both weather and tourism can affect them greatly. But it's been hard not to notice what's been missing from these discussions: climate change.

This oversight is particularly glaring given that this isn't the first of Puerto Rico's bioluminescent bays to go dark in the last year. Grand Lagoon – just a ferry ride away from Vieques in the town of Fajardo – went out for most of last November. The same explanations were debated then: unprecedented extreme weather events, or run-off from several nearby construction sites. No doubt either – or both – were contributing factors. But somehow, the conversation (at least in the media) never seemed to connect what was happening in Fajardo with global environmental concerns.

Given the ever-increasingly serious warnings about climate change – which 97% of climate scientists now agree is caused by human activity – it would seem to merit at least a small place in the popular discussion of these back-to-back mysterious ecological collapses.

Scientists who specialize in bioluminescent plankton have – to little fanfare – already warned us that these creatures are endangered. Two years ago, Dr Michael Latz, a researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, told New Scientist magazine that "as global warming changes ocean flows, these micro-organisms are increasingly at risk". Scientists atCanada's Dalhousie University showed that, since 1950, the worldwide population of phytoplankton has declined by 40% due to the rising sea surface temperatures caused by a warming planet.

We also know that the indirect effects of climate change have dangerous ramifications – the likes of which we are only just beginning to comprehend. Those strong winds and extreme weather events that have buffeted the bays? Increased sea surface temperatures – driven by climate change – may contribute to them as well, as we know from studying hurricanes. "The intensity, frequency, and duration of North Atlantic hurricanes ... have all increased since the early 1980s" reports the 2014 Third National Climate Assessment: "The recent increases in activity are linked, in part, to higher sea surface temperatures."

Like a pot being brought to boil, the seas are heating up.

The first time I visited Vieques in 2006, tour operators encouraged me to swim and kayak in the bay, but told me to avoid the motorboats, since their dirty engines created diesel-fuel dead zones. Since then, locals have developed new conservation guidelines: no swimming or touching the water with your skin at all – things I wish I had known not to do. But these and other protections have done nothing to save the bay's famed bioluminescent organisms.

But this isn't just about one or two tourist attractions on small islands in the Caribbean. Bioluminescent bays are rare because they are much more fragile than your average marine ecosystem. Like canaries in the proverbial coal mine, their loss is a warning that hardier creatures and more common shores will be endangered soon.

I was taught in elementary school that we live in a world with five oceans – an idea that feels laughable now. There is only one ocean – the world ocean, a vastness that ignores the political demarcations of maps and men. Its problems cannot be solved piecemeal, and more and more studies suggest that we might not "solve" them at all. Long before we detonated the first nuclear bomb or undertook a Cold War, nature invented the idea of mutually assured destruction – and she might just hold true to her end of the bargain.

If we are to do anything to begin to address the problem we have created, it will require a clear-eyed look at its true magnitude, and an understanding of the interconnectedness of our world – and its waters. Environmental concerns must be integrated into personal, political and commercial decisions on every level. We can no longer pretend that our trash disappears forever when it hits the wastebasket, or that we are not implicated in the environmental degradation of the far-away countries who now supply our ravenous need for consumer goods.

The phrase "think globally, act locally" might be mocked for its utopianism, but it's a mantra we need to heed when it comes to the environment. Otherwise the lights will continue to go out, in Vieques and around the world.

I don't even have a good picture of the Vieques bio bay to remember it by – like all real magic, it looks shoddy in reproduction. Perhaps, like the Grand Lagoon, it will come back, at least this time. But how often must nature flip the switch before we start paying attention?